Jon Manchester, CFA, CFP® (Senior Vice President, Chief Strategist – Wealth Management, and Portfolio Manager – Sustainable, Responsible and Impact Investing) shares his perspective on the changing economic landscape both at home and abroad.

March 31, 2022

Billy Joel’s Grammy-nominated hit “We Didn’t Start the Fire” was released in September 1989, months after the Soviet Union ended a nearly decade-long occupation of Afghanistan and amidst the steady crumbling of the once formidable USSR empire. At a staccato pace, the song journeys through a historical period that happened to roughly cover the Cold War era, a little over four decades of tumult and strife interwoven with great strides for humanity. Over 30 years later, watching Russian tanks roll into Ukraine—a former Soviet republic—one could imagine the song’s timeline stretching forward to encompass a new set of globally momentous events. The fire is clearly still burning, as another Cold War (or worse) seemingly gets underway.

Geopolitical risk is nothing new to the markets, but to see a brutal, unsparing ground war unfold in the digital era is nonetheless highly disconcerting and a shock to the interconnected global economy. It has the potential for long-lasting ramifications: generational-type economic setbacks for Russia and perhaps even enabler countries. Larry Fink, BlackRock’s long-tenured CEO, put it simply in his 2022 letter to shareholders: “…the Russian invasion of Ukraine has put an end to the globalization we have experienced over the last three decades.”1 Whether permanent shifts occur in cross-border economic activity remains to be seen. In the short-term, companies and nations are scrambling to distance themselves from Russia. Importantly, the European Union pledged to cut natural gas imports from Russia by two-thirds over the course of 2022, and phase out entirely by 2027.2

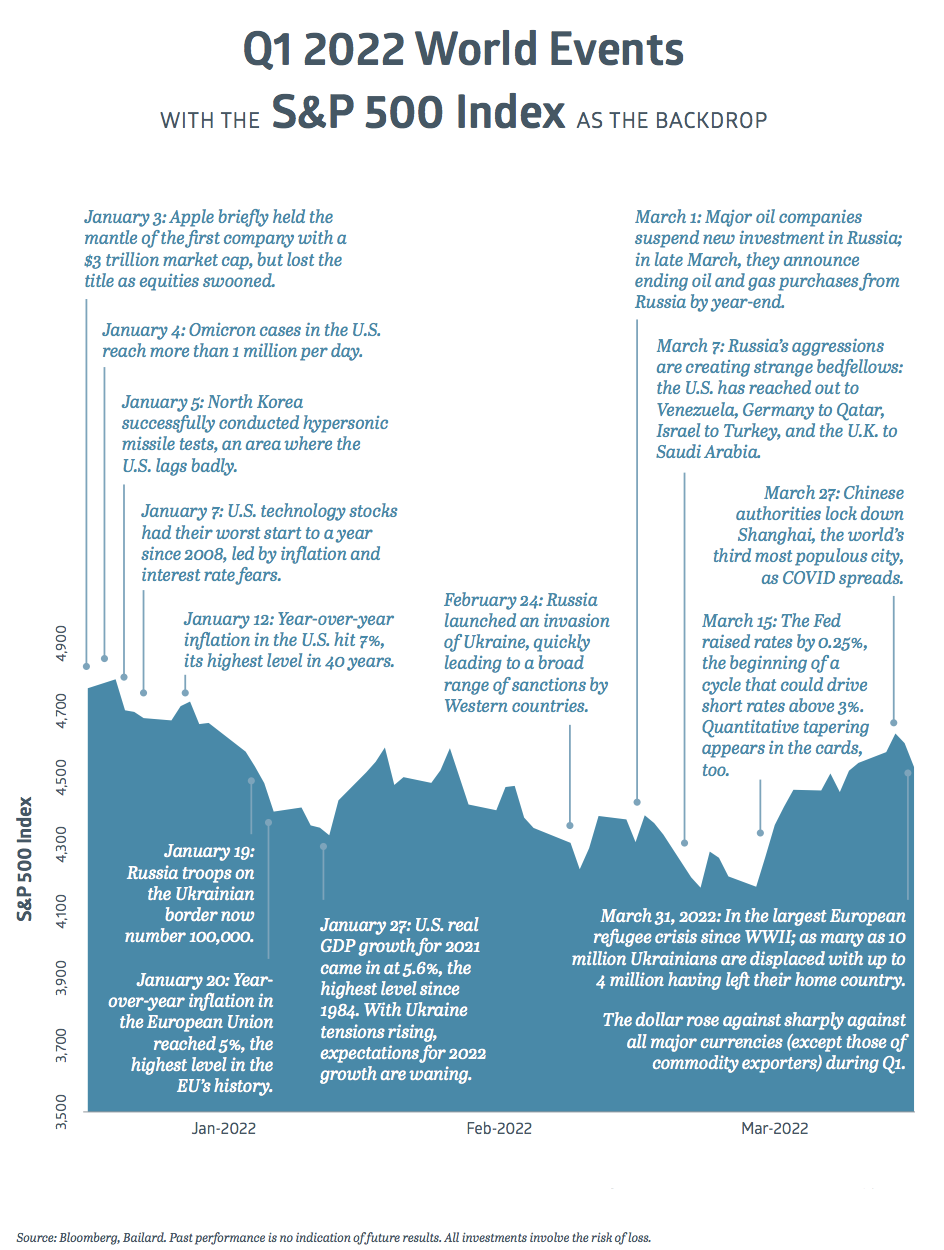

We have been through a lot over the past 24 months, yet largely we’ve been here before in some form, whether it’s Russia invading or Afghanistan changing hands or even the flu pandemic a century ago. Today’s particular mixture of unstable elements may be new, but Billy Joel’s lyrics are in a sense timeless, a reminder that progress is at best a rocky road. The financial markets seemed to recognize this in the first quarter, reacting more negatively to news of higher inflation and interest rates than bombs and bloodshed. In fact, the major U.S. equity indices traded higher from the point Russia invaded on February 24 until the quarter ended. The S&P 500 Index gained 5.6% price-only in that timeframe, trimming its Q1 loss after a tech-driven selloff to begin 2022, and adding a data point in favor of the old “buy on the cannon” adage.

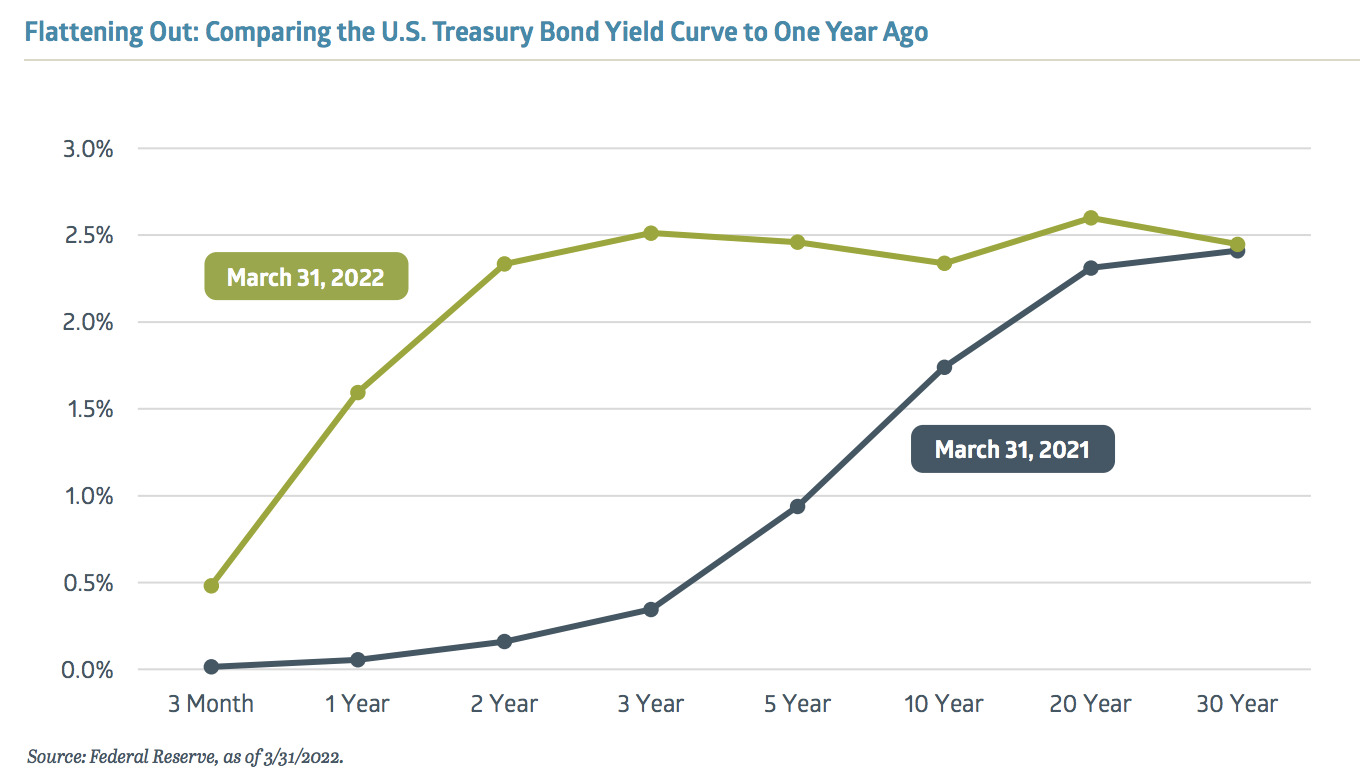

Markets are sending largely cautionary signals as geopolitical turmoil swirls and investors attempt to divine the future for inflation and interest rates. The U.S. Treasury yield curve – which is more of a straight line at present from two years out – had just 0.11% separating the 30-year and 2-year notes when Q1 finished. Some parts of the curve have inverted recently, meaning the yield offered for the shorter maturity (2-year, e.g.) was higher than the longer maturity (10-year, e.g.). Historically, an inverted yield curve is a recession warning sign, albeit an imperfect one. Investors who fled to the relative safety of bonds suffered historically poor returns in the first quarter as rates moved higher: the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index declined 5.9%, its largest quarterly loss since 1980.3

Equity investors were more ambivalent, but ultimately all the major equity indices declined, with international markets faring modestly worse than domestic ones. Value easily outperformed Growth, a continuation of a trend we saw in 2021 within the U.S. mid-cap and small-cap categories, but a reversal for large-cap. Only two S&P 500 sectors rose in the first quarter: Energy and Utilities. West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil jumped 33% to $100 per barrel, taking the Energy sector along for the ride, after reaching a closing high of almost $124 earlier in March. Higher crude oil prices translate into elevated input costs across the economy, a headwind for other sectors. Utilities are typically viewed as steady businesses that hold up relatively well in economic slowdowns. Therefore, it wasn’t particularly encouraging to see either of those sectors atop the Q1 leaderboard. In addition, the S&P 500 Banks industry group sank 8.1% on a price-only basis, a sign that investors may be assigning a higher probability to a more severe economic slowdown. The Conference Board estimates that U.S. Real GDP (Gross Domestic Product) growth will slow to 3.0% in 2022 from 5.7% last year.4

Shrinkflation

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 7.9% in February relative to one year earlier, with Core CPI (ex-food & energy) not far behind at an increase of 6.4%. Inflation hadn’t run this hot since January 1982, and higher gasoline prices accounted for about one-third of February’s increase. Global supply chain struggles persist, complicated further by war in Ukraine. One bit of good news, at least to economists, is that April 2021 marked the last month of less than 5% year-over-year CPI growth readings, setting up for at least tougher comparisons as 2022 unfolds. That will be of little consolation, however, if inflation continues to become entrenched across the economy.

Of chief concern is wage inflation, which grew at 5.6% year-over-year in February, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell admitted in March that the job market is “tight to an unhealthy level,” with more than 1.7 job openings for every unemployed person. The March 2022 unemployment rate was just 3.6%, nearly identical to the pre-pandemic February 2020 rate of 3.5%. There are encouraging signs regarding labor force participation. The participation rate for the key 25 to 54 years-old demographic continued to edge higher, hitting 82.5 in March, just below the 83.0 level from February 2020. For the 55+ years old cohort, the labor participation rate is likewise heading north, easing some of the “great resignation” worries. If these trends continue, wage inflation should moderate and avoid the dreaded wage-price spiral.

In the meantime, companies continue to find ways to combat rising costs. Last year, Frito-Lay reduced its standard-size Doritos bag by half an ounce, or the equivalent of five chips. The price of the bag remained $4.29, however. The term for this is shrinkflation, referred to as inflation’s “devious cousin” by NPR.5 This practice of package downsizing is common in the food industry, and has been for a long time. Nabisco dropped two ounces from its family size Wheat Thins box, a loss of 28 crackers, and akin to a 14% price increase. Although not a new phenomenon, shrinkflation tends to increase with cost pressures. When online news organization Quartz reached out to Frito-Lay about the scaled-down Doritos bag, a representative said: “Inflation is hitting everyone…we took just a little bit out of the bag so we can give you the same price and you can keep enjoying your chips.”6 That sounds like a win-win proposition, until you get to the bottom of the bag and find yourself five chips short of satisfied.

Finally Fed Up

We have liftoff, at last. In March, the Federal Reserve took its first step toward normalizing monetary policy by increasing the target Fed Funds rate to the 0.25% to 0.50% range. This came two years after the Fed slashed the lower end of the target range to 0% in response to the pandemic onset. Prior to the pandemic, the Fed had cut three times in 2019 despite acknowledging at the time that the “labor market remains strong” and with inflation stable – although arguably too low given the Fed’s 2% inflation objective.7 The bias has clearly been to support economic growth and allow inflation to move higher, the latter of which was formalized in 2020 via the Fed’s new “average inflation targeting” policy.

With inflation now at a 40-year high, naturally there are questions. To be fair to the Fed, they couldn’t anticipate the pandemic and the supply chain issues that have resulted. However, it does seem as though the Fed could have moved off their “zero interest rate policy” (ZIRP) last year, with the economy in recovery mode and vaccine adoption reasonably widespread. Maintaining the Fed Funds rate at zero is really meant for emergency periods, economically speaking, and the Fed has perhaps been too cavalier about using this approach. They now run the risk of policy error with inflation running ahead of their ability to tame it.

The current expectation is that the Fed raises aggressively over the remainder of 2022, at all six remaining meetings, taking the target range up to 2.25% to 2.50%. Will this be enough to cool down inflation? The bond market thinks so: current rates for inflation-linked U.S. Treasuries imply annual inflation of 3.4% over five years compared to 5.6% over the next year.8 Chairman Powell pointed to several “soft landings” of the past, instances where rates were raised without tipping the economy into recession. Raymond James economist Scott Brown noted that tighter monetary policy won’t do much to help the supply chain, but demand should be slowed, and with aggressive Fed action required the economy may slow more than intended.9

A high inflation, slow growth economic environment would likely prove challenging for equity and bond investors alike. Corporate earnings have been resilient thus far, with S&P 500 Index operating earnings projected to climb 8% this year to $225 per share. Based on that estimate, the Index traded at a still lofty 20x forward earnings when Q1 wrapped up. With inflation running hot and interest rates presumably heading higher, we should see U.S. large-cap valuations go lower, leaving it up to corporate profits to maintain pace. Equity valuations in other categories remain more favorable, with the S&P MidCap 400 Index, S&P SmallCap 600 Index, and MSCI EAFE Index all clustered around 14x forward earnings. The MSCI Emerging Markets Index trades at closer to 12x earnings.

Following three straight years of strong returns, equities may need a breather in 2022. The odds of a recession are on the rise yet remain low in the short-term. New fires will break out as the world is turning, testing the altered global economy’s resilience and the tools we have to fight them.

1 “Larry Fink’s 2022 Chairman’s Letter,” www.blackrock.com, 3/24/2022

2 “Will the Ukraine War Spell the End of Globalization?”, www.nytimes.com, 3/30/2022

3 “Bond Market Suffers Worst Quarter in Decades,” www.wsj.com, 3/31/2022

4 “The Conference Board Economic Forecast for the US Economy,”www.conference-board.org, 3/10/2022

5 “Beware of ‘Shrinkflation,’ Inflation’s Devious Cousin,” www.npr.org, 7/6/2021

6 “How companies are hiding inflation without charging you more,” www.qz.com, 3/10/2022 7 “Federal Reserve issues FOMC statement,” www.federalreserve.gov, 10/30/2019

8 Source: Bloomberg, US Breakeven 1 Year and the US Breakeven 5 Year indices, as of 3/31/2022

9 “Weekly Economic Monitor – Soft Landings Are Hard,” www.raymondjames.com, 3/25/2022

Recent Insights

Quarterly Technology Equity Strategy Q1 2025

The Bailard Technology Strategy posted a 1Q25 total return of -9.35% net of fees—ahead of both the benchmark index (S&P North American Technology Index) and the competitor-comprised benchmarks. The Morningstar U.S. Open End Technology Category returned -9.98% and the Lipper Science and Technology Fund Index returned -10.88%, while the S&P North American Technology Index returned -11.43%. Over longer time periods of 3, 5, and 10 years, the Strategy’s net returns continued to lead the competitor’s peer benchmarks—quite substantially, as seen in the table to the right.

Despite market volatility in Q1, we have not significantly altered our positioning. Our view is that nothing is broken in tech, and we remain convicted in our investment process. With prices and valuation changing dramatically, we expect to optimize our positioning by bolstering or adding high-quality companies trading at attractive discounts to long-term value. We anticipate stabilization in industry fundamentals and fiscal policy in the latter part of this year.

April 16, 2025

Quarterly Small Value Strategy Q1 2025

Policy uncertainty, mixed economic and inflation numbers, and a declining stock market prompted investors to opt for the perceived safety of large cap stocks in the first quarter. Though trade wars disproportionally hurt larger cap stocks due to their much greater international exposure, and the new administration’s proposed deregulatory initiatives relatively help smaller companies, fear of recession eclipsed any other rational analysis during the period. As a result, small cap stocks now appear to be discounting a severe recession based upon price declines, while large cap stocks are barely discounting a mild one.

April 15, 2025

Keep Informed

Get the latest News & Insights from the Bailard team delivered to your inbox.