Why so many IPOs have been delayed in 2019, and why the typical investor may be better off without them.

Thomas J. Mudge, III, CFA, Senior Vice President and Director of Domestic Equity Research

September 30, 2019

2019 was expected to be a year filled with high profile Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) and—while there have been quite a few so far including Uber and Lyft—the timing of many others is now uncertain. To understand why, it helps to know a little more about the public offering process and a lot more about human nature.

IPOs are how some private companies raise investment capital by issuing new shares of stock to the general public. For most people, the best way to sell a house is through a realtor. You will receive professional advice regarding pricing, staging, etc. and your house will be presented in the best possible light to a broader array of potential buyers than you could ever discover on your own. Similarly, for most private companies, the best way to go public is through an investment bank and for the same reasons.

While realtors host open houses to entice buyers, investment banks hold road shows. In each case, euphemisms flow like water and never is heard a discouraging word. For houses, “charming” or “quaint” means tiny, “move-in ready” means vacant, and “easy access” means next to the freeway. For IPOs, the phrases are slightly less predictable but of a similar nature. “Focused on gaining market share” means striving for profitability, “disruptive” means hoping to change potential customers’ established buying habits, and “exploiting big data” means gathering reams of information that may or may not have an ultimate payoff. In both the real estate and IPO markets, this pre-sale hype by third parties is designed to boost buyer/ investor interest, increase the ultimate sales price, and justify their healthy fees.

While realtors host open houses to entice buyers, investment banks hold road shows. In each case, euphemisms flow like water and never is heard a discouraging word.

Why should the nature of IPO roadshows be of interest to prospective investors? A large driver of future stock returns is the difference between investor expectations and actual company results. In the case of IPOs—where the company hoping to go public is being expertly touted to investors in meetings across the country—expectations are naturally going to be high. In the case of certain private companies where investors are already somewhat familiar with their product (Uber and Lyft), expectations can run even higher.

While some IPOs outperform the overall stock market, on average, they have been a poor investment for the typical investor. A study by Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA) created an equally-weighted portfolio of all IPOs in the U.S. from 1992 through 2018. Each IPO was purchased on its second day public and held for an entire year. This IPO portfolio underperformed a well-known cap-weighted index of 3,000 stocks by 2.2% per year.

Sharp eyed readers may ask, “What about the first day an IPO trades publicly?” It is true for reasons beyond the scope of this column that, on average, IPOs outperform the market substantially on their first trading day. Professor Jay Ritter, University of Florida Eminent Scholar, maintains an IPO database that indicates, over the past 40 years, the average IPO gained 18% on its first trading day. This outperformance swamped the underperformance shown in the DFA study, so why not just buy an IPO on the first day it trades?

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. First-day IPO allocations are like the swag bags handed out at celebrity events to which you are never invited. It’s great if you find yourself the lucky recipient, but they’re very difficult to get your hands on. And unlike celebrities who can do as they please, the institutional investors allocated IPO shares in advance must hang onto those shares, often far longer than they may wish, in order to be included in upcoming IPO allocations.

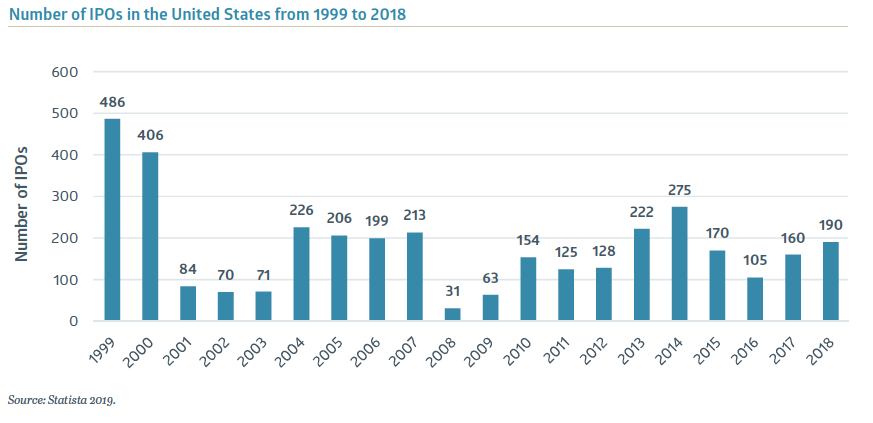

While the domestic IPO market has averaged over 220 deals annually over the past 30 years, there has been significant fluctuation in the number of IPOs from year to year. Appetite from the usual (non-first day allocated) investor for IPOs waxes and wanes based upon general market conditions and recent experience. While hardly anyone wants IPO stock when the overall market is falling, enthusiasm is also typically shaped by how well recent deals have performed and if any IPOs have been withdrawn.

First-day IPO allocations are like the swag bags handed out at celebrity events to which you are never invited. It’s great if you find yourself the lucky recipient, but they’re very difficult to get your hands on.

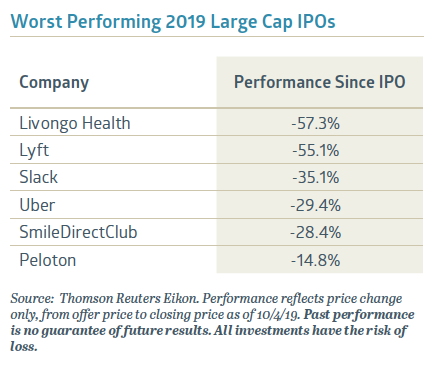

So far in 2019—while the overall stock market has remained healthy—investor IPO-specific zeal has taken several hits. Many highly-visible IPOs are trading well below their first day prices, and one of the most anticipated IPOs of the year (We Company, parent of WeWork) has withdrawn its IPO entirely.

Some view WeWork’s difficulties as a unique situation and not more broadly indicative of general IPO appeal. Wishful thinkers hope WeWork’s withdrawal is the equivalent of an old, sickly canary who was on the verge of collapse anyway, and not a problem with the air in the coal mine. While WeWork does have numerous distinct problems (a self-dealing former CEO and an asset-liability mismatch, among others), we believe it shares many common traits with other members of the 2019 IPO class.

A major shared characteristic among many recent IPOs is that they are launching entirely on the virtue of future expectations. Back to Mr. IPO: according to Professor Ritter, “it was unusual for a prestigious investment banker in the 1960s and 1970s to take a firm public that did not have at least four years of positive earnings. In the 1980s, four quarters of positive earnings was still standard. In the 1990s, fewer and fewer firms met this threshold. Still, the investment banking firm’s analyst would normally project profitability in the year after going public.”

Today, with many IPOs, profitability is expected to be more than a year or two away. This is beyond the “all sizzle and no steak” category to the point of being “no steak, but hoping for sizzle once we get the grill assembled.”

As with any institution based upon hope and faith, it is helpful to not to have that faith tested too severely. The failure of one IPO—and the underperformance of many others—leaves the prospective IPO market vulnerable, particularly when the typical company coming public is offering mostly dreams of profitability somewhere down the road.

It appears that the difficulties of recently launched or withdrawn IPOs may force the delay of other companies wishing to tap into the public markets this year. This is probably good news for the average investor, as the temptation of an initial public offering is easier to resist when it is absent entirely.

Recent Insights

Bailard CEO Ft. in Forbes, “Three Ways To Put Your Values And Your Team First In A Competitive Market”

Bailard's CEO Sonya Mughal, CFA offered three insightful ways leaders in the industry can fortify their culture and step up their communication practices to attract and retain high-performing teams.

May 2, 2024

Country Indices Flash Report – April 2024

The Japanese yen hit its lowest level versus the dollar since the 1980s late in the month, followed by a sharp bounce in the currency, which most suspect was driven by official intervention.

April 30, 2024

Quarterly International Equity Strategy Q1 2024

The global economic environment changed dramatically in the first quarter as bond yields, which had marched down in the 4th quarter on the belief that central bank pivots were fast approaching, reversed course. Prospects for mid-year reductions in short-term interest rates remain high for Europe and the UK, but persistent strength in the U.S. labor market has pushed prospects for a shift there closer to the end of 2024. Still, non-U.S. equities found purchase in solid earnings even as they faced headwinds from a strong dollar due to the evolving central bank dynamics and heightened geopolitical risks. As noted below, we see a range of foreign stocks that can flourish in the current environment and remain excited for the potential of stocks both in developed and emerging markets to compete well against U.S. peers.

April 25, 2024

Keep Informed

Get the latest News & Insights from the Bailard team delivered to your inbox.