Linda M. Beck, CFA, Senior Vice President and the Director of Fixed Income

September 30, 2019

A country’s economic growth along with its savings rate depend upon its demographics. Younger workforces spend much of their income on major asset purchases like education, houses, and cars, among a myriad of other things. As a workforce ages, savings rates generally increase as more money is invested to fund future retirements. Once retired, retirees then draw down savings to pay for living expenses. This perspective—and exploring the average age of a country’s workforce—is helpful in determining the outlook for a country’s savings rate, which in turn has implications for interest rates.

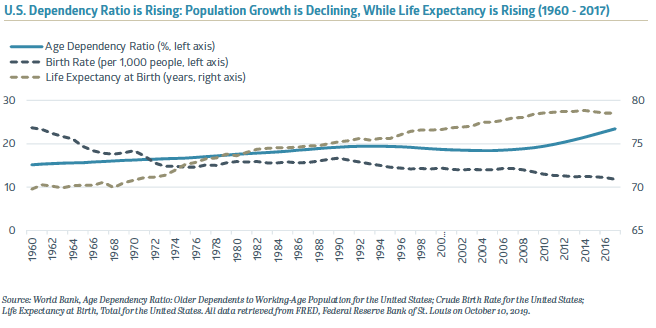

The aging of the U.S. and many other developed countries has been well reported. Since the early 1960s, life expectancy in the U.S. has increased by more than eight years while the birth rate has declined substantially. Everything else being equal, as a population ages, its labor force growth typically slows, usually triggering lower economic growth and lower interest rates. However, this typically occurs in tandem with a decline in savings rates, which then can push real interest rates higher. The net impact of these opposing forces depends on how the economy responds. If the economy can move from a less labor-dependent society to a more capital-dependent economy, then a higher interest rate environment may be maintained. An increase in productivity could enable economic growth to be maintained even with fewer labor participants.

Looking Ahead

Looking Ahead

Over the next decade, as more baby boomers enter retirement and barring other factors, a smaller pool of individuals in the labor force will be supporting a bigger number of retirees through entitlement programs such as social security and Medicare. A way to gauge this burden is to look at the dependency ratio, an age-population measure. The dependency ratio compares the number of individuals typically too young or too old for the labor force (those younger than 14 or older than 65) to those who normally are working (ages 15 to 64). Most developed countries have rising dependency ratios, which generally increase over time, all else being equal.

The domestic economy is certainly aging, but much of Europe and Japan already have higher dependency ratios than the U.S. It may take another ten years for the U.S. to reach the same ratios as Europe is experiencing today. Similarly, Japan has experienced an exceptional increase: since the 1990s, Japan’s dependency ratio tripled. Although demographics were just one factor behind this increase, Japan’s savings rate fell from 19% in 1995 to 7% in 2015.

And now, at least for the next decade, many economists predict that the impact from slower economic growth will outweigh that from reduced savings, resulting in lower than normal interest rates globally.

A Complicated Projection

It should be noted that many factors complicate such projections. The situation can change if governments increase savings to meet future entitlement obligations or if businesses issue less debt in anticipation of slower future economic growth. Additionally, disequilibrium between global savings and investments can impact the level of real interest rates. In the 2000s, Ben Bernanke, Chairman of the Federal Reserve (the Fed) espoused the idea that real interest rates were low due to a rapid buildup of savings in emerging market economies. Many of these emerging market economies had younger populations than developed economies. And today, China, for example, continues to have a high savings rate. Since China is still growing more strongly than most other countries, total global savings may increase despite declining savings in the U.S. and other developed countries. Developments in labor-saving technologies and automation can also strongly impact productivity. These technological advances are one of the ways in which economic growth may be sustained even with a smaller workforce.

Many economists predict that the impact from slower economic growth will outweigh that from reduced savings, resulting in lower than normal interest rates globally.

Economic Growth in Comparison to Debt

Since the credit crises, most global economies have experienced more modest growth. Slow real growth is one of the factors constraining interest rates to their currently-low levels. However, modest growth can pose a problem in leveraged economies, particularly if the interest on the debt exceeds economic growth. While the private sector has deleveraged some since 2008/2009, this has been replaced by public sector leverage. The large amount of sovereign debt that has been issued concerns many investors.

The U.S. moved from a budget surplus under Bill Clinton’s Presidency, to an almost $1 trillion deficit in 2019, roughly 4.2% of GDP. The deficit is projected to average 4.4% of GDP over the next ten years to 2029, significantly larger than the 2.9% GDP average over the past 50 years. With $22 trillion in total federal debt, the domestic debt-to-GDP ratio is about twice as high as the U.S.’s 50-year average. The interest due on that debt adds to the deficit each year and, for the time being, low interest rates have kept servicing the debt manageable. Whether investors continue to have a strong enough appetite to buy our public debt depends on the savings rates, the belief that the U.S. Treasury bonds are some of the most secure bonds in the world, the outlook for alternative investments, and geopolitics among other factors.

High government debt risks reducing private sector borrowing and reduced private sector borrowing could constrain growth. Additionally, high levels of government debt can make it harder for governments to respond to unforeseen crises in the future, potentially making any recessions more painful. If creditors become concerned about the U.S.’s debt growing too large or our ability to pay off that debt, this would cause interest rates to rise. Such a scenario could create a vicious cycle where debt burdens are increasing as economic growth falters, fueling a larger burden. However, we believe currently-weak global growth, the massive amount of negative yielding debt abroad, and a continued appetite for U.S. Treasuries should continue to keep real interest rates in the U.S. low over the near term.

Recent Insights

Bailard CEO Ft. in Forbes, “Three Ways To Put Your Values And Your Team First In A Competitive Market”

Bailard's CEO Sonya Mughal, CFA offered three insightful ways leaders in the industry can fortify their culture and step up their communication practices to attract and retain high-performing teams.

May 2, 2024

Country Indices Flash Report – April 2024

The Japanese yen hit its lowest level versus the dollar since the 1980s late in the month, followed by a sharp bounce in the currency, which most suspect was driven by official intervention.

April 30, 2024

Quarterly International Equity Strategy Q1 2024

The global economic environment changed dramatically in the first quarter as bond yields, which had marched down in the 4th quarter on the belief that central bank pivots were fast approaching, reversed course. Prospects for mid-year reductions in short-term interest rates remain high for Europe and the UK, but persistent strength in the U.S. labor market has pushed prospects for a shift there closer to the end of 2024. Still, non-U.S. equities found purchase in solid earnings even as they faced headwinds from a strong dollar due to the evolving central bank dynamics and heightened geopolitical risks. As noted below, we see a range of foreign stocks that can flourish in the current environment and remain excited for the potential of stocks both in developed and emerging markets to compete well against U.S. peers.

April 25, 2024

Keep Informed

Get the latest News & Insights from the Bailard team delivered to your inbox.