Linda M. Beck, CFA is a Senior Vice President of Bailard and Director of Fixed Income

June 30, 2019

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) had a significant impact on the supply, demand and relative value of municipal bonds. The TCJA reduced taxes for many Americans by raising the standard deduction, doubling the child tax credit and reducing the top personal

marginal tax rate. However, it also capped the amount of state and local tax deductions (SALT) and curtailed the mortgage interest deduction. The Act slashed corporate income tax rates and virtually eliminated tax-exempt advanced refundings for municipal bonds.

The Effect on Demand for Municipal Bonds

For roughly 65% of Americans, the TCJA did generate tax cuts; although at an average of only $1,200, the tax cut was less than the $4,000 advertised by the Trump Administration. The top marginal tax rate was cut from 39.6% to 37.0%. Normally, lower tax rates would translate to decreased demand for tax-free municipal bonds; however, this decline was too small to impact demand. In fact, the cap on the SALT deductions and the curtailment of the home mortgage interest deduction led many investors in high-tax states to increase their municipal bond purchases. Prior to the TCJA, taxpayers in California, New Jersey and New York claimed an average SALT deduction of over $17,000. The cap eliminated about 40% of this average deduction, and negatively impacted approximately 11 million taxpayers. With the changed deduction rules, owning municipal bonds became one of the few remaining

ways to reduce tax payments to the federal government.

The TCJA also dramatically reduced the number of taxpayers who pay the individual alternative minimum tax (AMT). Prior to the Act, the number of individuals paying the AMT grew as the tax system was adjusted for inflation, but the dollar threshold for the AMT was not. Over time, when Congress lowered individual tax rates, they lowered normal tax rates but not the AMT rates, so more and more Americans became subject to the tax. The TCJA reduced the number of taxpayers subject to the AMT from about five million to only about 200,000 currently. This adjustment, as well as the SALT cap and limit on mortgage interest are all set to end by 2025. Higher taxes for individuals in high-tax states, along with this year’s more dovish stance by the Federal Reserve and a slowing economy, have further stoked bond purchases. Municipal bond mutual funds have had positive flows every week in 2019, and inflows into municipal funds totaled $36.8 billion through June 30, making this the third largest annual net inflow ever and the highest inflows in the first half of the year for nearly three decades.

Municipal bond mutual funds have had positive flows every week in 2019, and inflows totaled $36.8 billion through June 30.

Although the changes in the tax code—coupled with the current monetary and economic environment— increased the demand for municipal bonds, the change to the corporate tax rate offset some demand. Insurance companies and banks have traditionally been big buyers of municipal bonds (owning about 28% of all outstanding municipals). The TCJA cut the top U.S. corporate tax rate from 35% down to 21%. This brought the U.S. rate below the average for most other Organizations for Economic Co-operation and Development countries. With lower taxes, many insurance companies and banks were less motived to buy tax-exempt bonds. That said, these companies have other reasons for holding their municipal bonds aside from the tax advantages. These include low correlation with other assets, low default rates and built-up income through “book yield” portfolio management.

Supply Changing Too

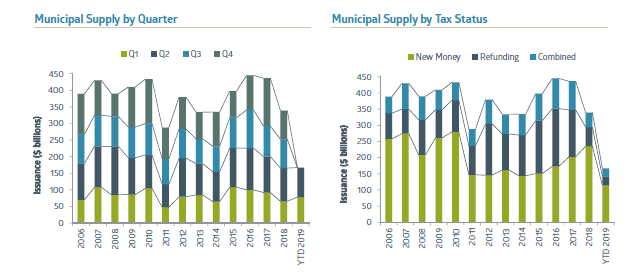

While the TCJA stimulated demand for municipal bonds, it also reduced supply. The TCJA eliminated the ability of municipalities to advance refund bonds. Before the Act, municipalities would issue new bonds to pay off another outstanding bond, in order to lower

borrowing costs when interest rates declined. The TCJA made the previously tax-exempt interest on advance refunding bonds taxable, all but eliminating the appeal. Advance refunding issuance, which typically accounts for about 20% of bond issuance, largely disappeared starting in 2018. As seen in the graphs below, 2018 municipal supply dropped 25% from the prior year. Evaluating the supply by tax status reveals that refunding volume also decreased in 2018, by 60%. Supply in 2019 has thus far been continuing at a low

level. Despite significant infrastructure and capital needs, many municipalities are not issuing bonds as they try to keep spending in line with tax revenues. Cash flow from tax revenues is positive but constrained, as revenues flow from the slowly-expanding economy. Any hopes of new major infrastructure projects (which could increase bond issuance) are fading as current plans have reached a political impasse.

Looking at the Fundamentals of the Municipal Credit Market

Municipal credit fundamentals are positive, with tax receipts flowing in from the long period of economic growth. Positive credit fundamentals, in concert with strong demand and with low supply, have been driving up the market value of municipal bonds. One way to gauge the value of municipal bonds relative to other securities is to compare yields of AAA rated municipal bonds with yields of relatively risk-free U.S. Treasury bonds. By dividing the yield of AAA municipal bonds by similar maturity “risk-free” Treasuries, you can gauge their relative value. At the start of the year, this ratio for 10-year securities stood at 85%, close to its

long-term (30-year) historical average. A ratio of 85% means that anyone paying in excess of a 15% federal tax rate would obtain more after-tax income by owning a municipal bond rather than a Treasury. However, investors generally demand a higher after-tax yield on

municipals than treasuries to compensate for the lower liquidity and higher credit risk of municipal bonds.

As demand continued to increase in 2019 and supply remained tepid, this supply/demand imbalance drove the relative value ratio down to 73% by April. Municipal ratios for short-dated maturities are typically even lower than for longer-dated maturities. As these ratios

reached low levels through much of 2018 and 2019, it was often profitable for even the highest-taxed investors to diversify into either Federally-taxable (but still state tax free) municipal bonds or to purchase corporate bonds (which are subject to both federal and state tax). At low ratios, diversifying into these other bond sectors boosted investors’ after-tax income, even when paying the taxes.

Municipal bonds issued by high-tax states (think California, New York and Oregon) have richened significantly relative to similarly-rated bonds issued out-of-state. This is due to extremely high demand from in-state investors seeking the shelter of double tax-free income. As of June 30, short-dated municipal bonds issued in California were trading at about a 0.30% lower yield than out-of-state bonds.

Investors can also add yield to their portfolios by buying bonds subject to the AMT. With so few investors now being subject to the AMT, more individuals can buy the bonds without a tax penalty. These private activity bonds typically yield 0.25% to 0.35% more than similar rated non-AMT bonds. Investing in bonds maturing prior to the 2025 (when the AMT revision ends) is particularly attractive.

Longer term, the aging of the U.S. population and the wave of retiring baby boomers should add to demand for municipal bonds. The outlook for supply remains constrained unless a large infrastructure program gets approved and passed. These positive technical dynamics should keep municipal bonds trading at richer market values than otherwise; however, they remain an attractive investment for investors seeking relatively

stable tax-free income.

Recent Insights

Bailard Appoints Dave Harrison Smith, CFA, as Chief Investment Officer

Bailard is pleased to announce that, as of today, Dave Harrison Smith, CFA, has been promoted to Chief Investment Officer. He succeeds Eric Leve, CFA, who held the role for more than a decade and will continue with the firm as a portfolio manager, fully focused on international markets.

July 1, 2025

Country Indices Flash Report – June 2025

Tariff negotiations intensified as the July 9th reciprocal tariff deadline nears, though the Trump administration signaled flexibility on the cutoff for countries negotiating in “good faith.” The U.S. and China secured a high-level framework that included a key rare earths deal and a tariff truce extension to August 11th. Meanwhile, the UK finalized a 10% tariff rate after a threatened 27.5%; talks are swiftly progressing with the EU.

June 30, 2025

Mike Faust Awarded 2025 Advisors to Watch by AdvisorHub

Michael Faust, CFA, ranked in the top five of AdvisorHub’s Advisors to Watch for the second year—recognizing his standout leadership at Bailard.

June 24, 2025

Keep Informed

Get the latest News & Insights from the Bailard team delivered to your inbox.