Inflation is a word that tends to strike fear into consumers and investors alike. For Americans, the trauma of the last major inflationary period in the 1970s still resonates. But economists view inflation with a bit more nuance. The other side of the coin, deflation, is almost always bad. Deflation typically creates a vicious spiral of reduced spending—why buy it today when I can get it for less tomorrow?—that leads to lower production and a smaller overall economy.

Modest inflation in the range of 2% to 4%, depending on whom you ask, can stimulate economies in productive ways. For this reason, the Federal Reserve aims for a target inflation of 2% over the long run. If an economy is not running at full capacity (e.g., the current state in the U.S.), there is some combination of underutilized labor and other resources that the prospect of higher prices can draw in. As these resources are deployed, the economy produces more and becomes wealthier. Further, as the inverse of the deflationary story, consumers are motivated to spend sooner rather than later.

Importantly, some level of inflation is fundamentally necessary to motivate entrepreneurs to take the risk of investing for the future; higher prices will compensate for their near-term costs. The resulting technological progress increases the productive capacity of our economy, enhancing long-term economic growth prospects.

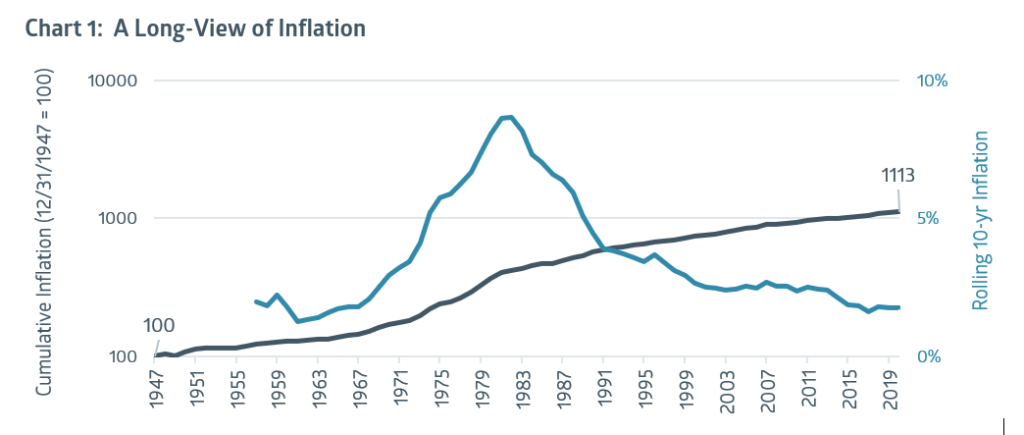

Source: U.S. CPI Urban Consumers |

Post-WWII, inflation has been a consistent feature of the U.S. economy. There are several critical takeaways from Chart 1:

- Inflation, at about 3.3% annually, has led nominal prices to rise 10x over this period.

- The periods coincident with the first and second oil price shocks (1973 and 1979, respectively) led to increased inflation. This generated a large spike that lasted nearly 20 years, even when looking at 10-year rolling inflation windows.

- Taking out the seven years between the two oil spikes brings the annualized rate of inflation over this period down to 2.7%.

- Since the early 1980s, the pace of inflation has moderated dramatically, bringing inflation in the past few years near its lowest in this 70-year history.

But inflation is only meaningful if it impairs consumers’ purchasing power. When wages are rising faster than inflation, purchasing power increases as has been the case over this same 70-year timeframe shown in Chart 2. Productivity increases have clearly supported this trend, helping enrich both labor and capital. Bottom line, our nation has become wealthier and, even though prices have risen a bit more than 3% per year, consumers have increased their purchasing power dramatically over the post-war period.

Source: U.S. Disposable Income Per Capita, Nominal Dollars |

All that said, investors remain rightly concerned: Will the unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus since March of 2020 lead us to another inflationary episode?

There is no question we are currently experiencing some transient inflation; the uncertainty is whether we have the ingredients that could lead it to become more permanent. Last spring, at the height of COVID-19 uncertainty, economic growth and prices fell dramatically. Now, in spring 2021, the year-over-year comparisons look impressive from a growth perspective but still a bit anxiety-provoking inflation wise. The U.S. economy in 2021 could generate real (inflation-adjusted) growth higher than any time in the past 25 or even 60 years. In short order, this will bring the U.S. economic activity above its heady pre-COVID-19 levels (December 2019) and even return to the growth trend then in place.

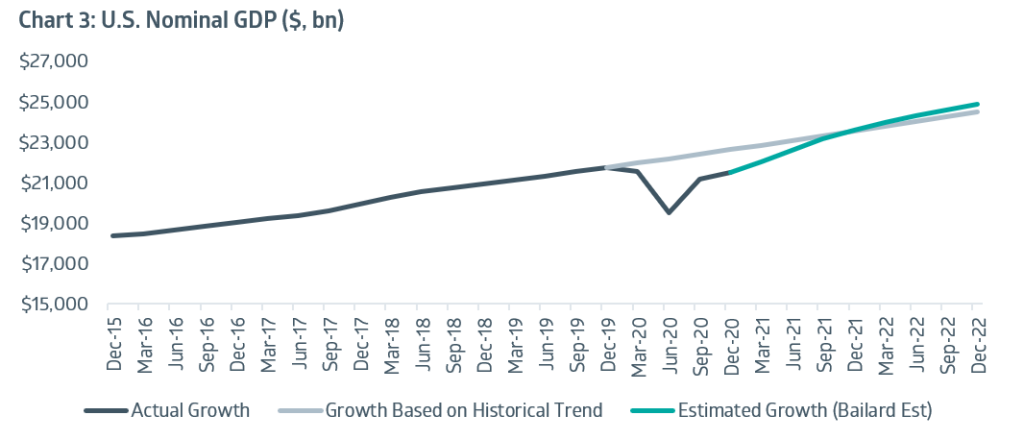

Source: U.S. GDP Nominal Dollars, Seasonally Adjusted. Bailard estimates. |

As reflected in Chart 3, total economic output should breach 2019 levels by this summer and potentially return to historical norms by early 2022. Currently, there are plenty of individuals outside the workforce who would like to join it. Likewise, at this stage of the recovery, some factories aren’t being utilized to the fullest extent. The question remains: If economic growth is about to expand at the rate we expect, isn’t it likely that those underutilized resources will be quickly reengaged, even pushing at their capacity? That is one tried-and-true recipe for inflation.

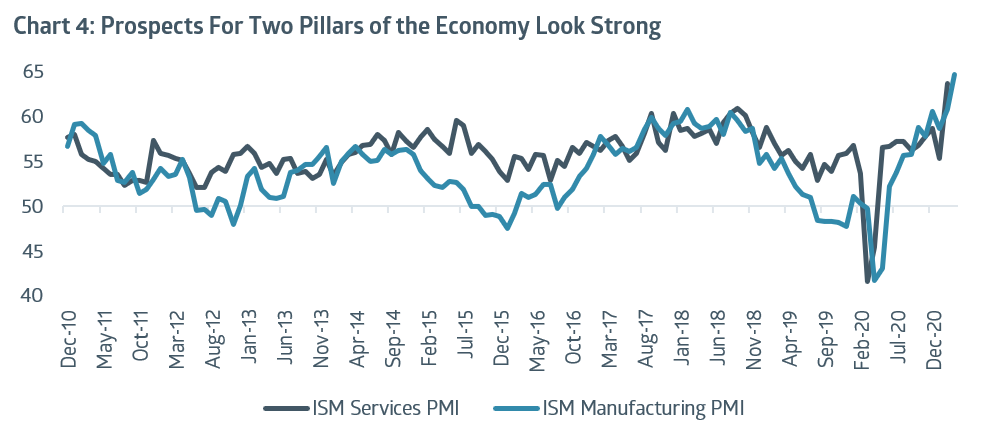

As shown in Chart 4, surveys of purchasing managers reflect huge optimism moving forward, even in the service sector which had been hardest hit over the past year. (These purchasing managers indices are what are known as diffusion indices; a level of 50.0 would indicate that there were equal numbers of optimistic and negative respondents.)

Source: Institute for Supply Management |

But even with this optimism, growth, and stimulus, are we pushing up against the constraints of our economy? In the short term, the answer is probably no. The utilization of our nation’s manufacturing capacity plummeted last spring but, even as the economy roars ahead, the current utilization rate of 73.8% is well below its long-term average of 76.2%. Apart from the last 12 months, capacity utilization is lower than any time in the past ten years.

Source: Federal Reserve, G.17 Report, April 15, 2021. |

The other major input that can stoke inflation is labor, and there we may push our economy’s limits much sooner. Wall Street analysts are deeply split over the path of the jobs market for the rest of 2021. Optimists envision we could soon enjoy increases of one million jobs monthly, pushing the labor market close to the tight state of the pre-COVID-19 period. Alternatively, continued concerns about in-person work could temper the trend, and continued supplemental unemployment benefits from the federal government may disincentivize some workers’ return to the labor market. New higher minimum wage laws could generate two distinct outcomes: Either inhibit hiring or marginally drive inflation higher.

As we consider the prospects for inflation, it is critical to recall that prior to March of last year, the U.S. economy had enjoyed the longest economic recovery in its history, lasting more than ten years. Unemployment had fallen to 3.5%, a 50-year low; capacity utilization was above its ten-year average; and inflation measured 2.3%, just slightly below where it stands today.

Our Inflation Outlook Moving Forward

We continue to envision higher inflation during much of 2021, given the combination of economic reopening, ongoing stimulus, and an accommodative Federal Reserve. The longer-term picture looks much as it did in the 2010s: structural forces, supported by increased labor productivity, working together to create a healthy level of inflation. The prospects of runaway inflation or stagflation remain very low.

Of course, the nuance remains. Considering all the elements cited, we would be remiss if we didn’t acknowledge an array of issues that could generate inflation beyond the level of “good inflation”:

- Deglobalization could lead to higher prices for goods. If companies choose to shorten their supply chains to reduce risks due to trade conflicts or pandemics, the costs of production for those and other goods could rise. That is, it would be cheaper to produce low margin items in China or Vietnam than in the U.S., but doing it domestically lowers supply chain risk.

- Bringing the “right” manufacturing that supplies the expected demand boom back online could be challenging. We could see bottlenecks for supplies that affect intermediate and consumer goods prices.

- Broadly, consumers have historically high levels of savings post the COVID-19 lockdown and Federal largess. It is hard to estimate the impact of unleashing that into spending.

- Taxes are deflationary. To the extent that expansive fiscal policy has set the stage for outsized economic growth, tax increases offset this. One mechanism of this is that it may lead consumers to spend less of their accumulated savings due an increased tax burden.

- To finance the government’s ongoing spending, it has taken on unprecedented amounts of debt and has allowed the money supply (M2) to grow by 28% since the end of 2019. So far, this has shown up in the price inflation of financial assets and homes, but it could impact the economy more broadly.

- The Federal Open Market Committee’s clear mandate—to pursue full employment coupled with its 2020 statement that they are willing to accept higher inflation to achieve a targeted goal over the long-term—may lead them to let inflation run longer than they might have historically.

- As discussed previously, inflation tends to occur primarily when an economy pushes too hard against its productive capacity. There is some belief that the technological changes of the past generation have increased our economy’s potential growth, leading to a longer runway before the economy could overheat.

- That said, another theory posits that inflation is mostly a psychological state built on a population’s expectations. If consumers and businesses begin to believe that inflation is likely, their actions could drive the economy toward it by building price increases into contracts and demanding higher wages moving forward. Since many U.S. investors, business owners, and consumers have no experience with inflation, they may too quickly discount its resurgence. If these cohorts are caught “flat-footed,” the inflationary response discussed above could be exaggerated.

Inflation may not be the dire taboo event some predict, but it certainly carries many subtleties. For the time being, we remain cautiously optimistic about the economy’s capacity to keep pace and mitigate negative outcomes.

The information herein is based primarily on data available as of its publication date and has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy, completeness and interpretation are not guaranteed. This publication has been distributed for informational purposes only and is not a recommendation of, or an offer to sell or solicitation of an offer to buy any particular security, strategy or investment product. This publication contains the current opinions of the authors and such opinions are subject to change without notice. Bailard cannot provide investment advice in any jurisdiction where it is prohibited from doing so.

All investments have the risk of loss. Past performance is no indication of future results.

Recent Insights

Bailard Appoints Dave Harrison Smith, CFA, as Chief Investment Officer

Bailard is pleased to announce that, as of today, Dave Harrison Smith, CFA, has been promoted to Chief Investment Officer. He succeeds Eric Leve, CFA, who held the role for more than a decade and will continue with the firm as a portfolio manager, fully focused on international markets.

July 1, 2025

Country Indices Flash Report – June 2025

Tariff negotiations intensified as the July 9th reciprocal tariff deadline nears, though the Trump administration signaled flexibility on the cutoff for countries negotiating in “good faith.” The U.S. and China secured a high-level framework that included a key rare earths deal and a tariff truce extension to August 11th. Meanwhile, the UK finalized a 10% tariff rate after a threatened 27.5%; talks are swiftly progressing with the EU.

June 30, 2025

Mike Faust Awarded 2025 Advisors to Watch by AdvisorHub

Michael Faust, CFA, ranked in the top five of AdvisorHub’s Advisors to Watch for the second year—recognizing his standout leadership at Bailard.

June 24, 2025

Keep Informed

Get the latest News & Insights from the Bailard team delivered to your inbox.